The Strategy Lab category is a new feature we’ll be adding here at Discipline Alerts. This will focus exclusively on portfolio construction and our views on how to optimize the portfolio construction and management process.

We’re big believers in the idea that simple is better. In general, the asset management industry has mastered the art of selling complexity in exchange for high fees. This often creates the illusion of sophistication and in reality results in inefficiencies. But in this piece we look at the other side of the coin – can simple be too simple?

One of the common themes I’ve written about over the years is that there’s no such thing as a truly “passive” investment strategy. That is, at the aggregate level the only truly “passive” portfolio is the entire market cap of stocks and bonds. An efficient market believer would buy that portfolio and rebalance back to it regularly to maintain this “efficient” market allocation, knowing that deviations are “active” decisions that essentially say “the market is wrong, I can do better”. The problem is, a fund like this isn’t even available primarily because most of the underlying assets aren’t investable. More importantly, every investor has a good reason for deviating from this allocation because every investor has different personal needs. So, for instance, the “market” portfolio might tell us to hold 45% stocks and 55% bonds, but maybe you’re a young and aggressive investor who wants to be 100% stocks because you have a very long investing duration. This is a perfectly reasonable reason to deviate from the market portfolio.

This raises another interesting question though – if you wanted to be 100% stocks why not buy one fund like Vanguard total world (ticker: VT)? Or, if you wanted to be diversified why not buy one fund like a target date fund or a 60/40 fund? I think there are many good reasons why this simple portfolio is too simple and actually creates complexity in your financial life. To be clear, this doesn’t necessarily mean these funds are bad. It just means that you invariably need other positions to compliment it for various reasons.

When simplicity creates higher taxes and fees.

In the vase of many one stop funds like VT you can actually replicate the same basic holdings with two funds (for instance, VXUS, Vanguard Ex-US and VTI, Vanguard Total US). Using these two funds creates marginally more portfolio complexity but actually reduces your fees and potentially increases tax efficiency. That’s because the aggregate expense ratio of a portfolio that’s 50% VXUS and 50% VTI is 0.05% vs 0.07% for VT. Additionally, using more holdings creates the potential for some tax loss harvesting across time because you can pick the specific components to be harvested. This means that using VT for your entire portfolio would create higher taxes and fees. Of course, this doesn’t mean VT is a bad holding. It just means that adding some components around VT can actually enhance certain elements of the management process.

One risk to be aware of in this process is the risk of performance bias. We diversify because we know that diversification works primarily because some part of the portfolio doesn’t always work. So VTI might outperform VXUS for long periods of time (as it has in recent decades). This isn’t necessarily a bad thing! We should expect the performance to ebb and flow and the grass will always looker in some part of your portfolio. But sometimes you need the grass to die back in some parts in order for the aggregate yard to be healthier in the long run. Good diversification is about learning to hate some part of your portfolio all the time.

Home Bias and Forced Activity

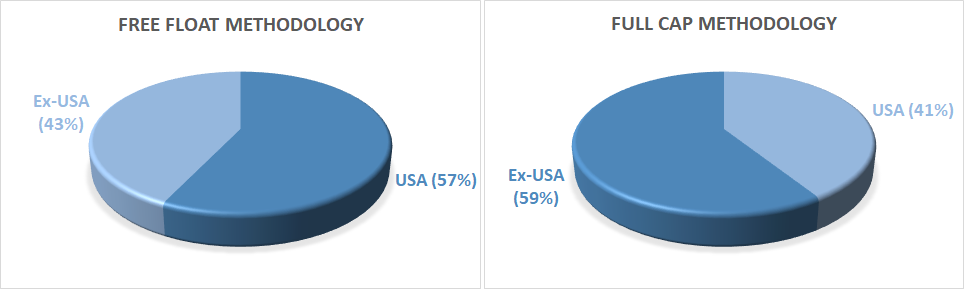

One of the most interesting aspects of many “one stop” equity or bond funds is that they’re rife with home bias and forced activity. For instance, the actual “full cap” market cap of global stocks is close to 60% foreign and 40% US. But a lot of that foreign market cap is not investable for various reasons. So funds like Vanguard Total World end up actually being closer to 60/40 US/International. This is very interesting because you are forced to be more active than the actual market cap of the global equity market simply because it’s more efficient to deviate more. But this also exacerbates the home bias of a US based investor. So in order to reduce this home bias you would have to deviate from VT, for instance, by building a 40/60 VXUS/VTI portfolio.

We’re big believers in reducing home bias primarily because we think it’s a reasonable (potential) cost to incur at times knowing that it’s operating as a small insurance hedge in various ways against domestic currency risk and US economic dominance.

Homogeneous Asset Class Risk.

Everyone is a multi-asset investor because of liquidity constraints. Even the most aggressive equity investor needs a cash allocation. And thinking of this concept in terms of a multi-asset portfolio (like stocks and bonds) creates other potential problems. The biggest of which is liquidity risk. For example, if you owned just one fund as a 60/40 portfolio you create a very simple, diverse and low cost portfolio. But as I discussed in my All Duration Investing paper, you also create one homogeneous asset that is similar to an instrument with a 12 year duration. So while the stock market is an 18 year instrument in our model you reduced the duration and volatility by adding aggregate bonds with a 6 year duration. But the sum of the parts still results in a fairly long duration instrument.

The beauty of owning a 60/40 (or any multi-asset portfolio) is that you reduce the overall volatility of the portfolio by throttling the stock risk. So, even in a year like 2022 when bonds performed poorly and a 60/40 had one of its worst years ever you still reduced the volatility of a 100% stock portfolio by 30% because you owned bonds which were far less volatile than the stocks were. This is a good thing because a less volatile position is likely to be one that is more behaviorally tolerable and help you stay the course. A countercyclical approach like the strategy John Bogle used throttled that volatility even more (12% for countercyclical, 16% for 60/40 and 23% for stocks).

On the other hand, a year like 2022 exposed an important problem in simple portfolios like this – the homogeneity of the portfolio creates this 12 year instrument. And if you needed liquidity in that 12 year instrument then you had to take a principal loss because the aggregated 6 year bond instruments were also negative. So, even though you technically owned some “cash” or short-term bonds in the 40% bond component of the portfolio you couldn’t go in and hand pick the liquid components because you have to sell some entire portion of the 60/40 to obtain the liquid part. This is inefficient because you’re selling stocks AND bonds lower. Instead, you needed the portfolio to obtain more complexity with a more liquid bucket like a cash or T-Bill bucket. This would have enhanced your liquidity and the behavioral robustness of the portfolio even though it added complexity. In our view there is a balance here. You can create something simple, but not too simple where you have assets for, you guessed it, All Durations.

Key Takeaways

The key message in all of this is that “passive” can actually end up being too passive because simple can be too simple. In our view, when we talk about “passive” investing we really mean that we’re being tax and fee conscious within the context of also maintaining a behaviorally robust portfolio that aligns with our actual financial plans. Some of that requires a bit of activity and that’s okay. A wise man once said “you have to break some eggs to make an omelette” and financial planning often means breaking up parts of our financial lives to make something more delicious.