One of the big lessons from the 2010-2020 environment was that headline payrolls could increase substantially without putting upward pressure on inflation. This can be confusing because there’s often an assumption that more jobs mean more demand and higher prices. But it’s more complex than that. Think of it like stock prices. Prices will rise when the eagerness of buyers outpaces the eagerness of the sellers regardless of the depth of the market. The same basic thing happens in the labor market. So, even if you have an increasing number of people working the cost of that labor can actually slow if capital has more negotiating power over labor. This is essentially the story of the entire decade of the 2010s when the labor market expanded by an average of 190K per month and inflation was 1-2% almost the entire time. That occurred, in large part, because capital had so much negotiating power over labor.

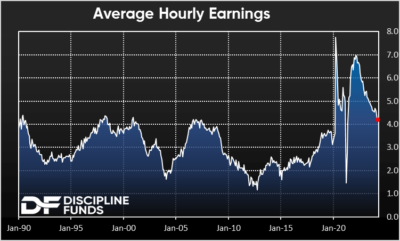

And the best way to see that relationship is in hourly wages. In short, does capital need to pay you more to work? And the obvious answer in the 2010s was no.

Importantly, the same trend is playing out now and Powell has been very clear about this. In the most recent press conference he said:

“in and of itself, strong job growth is not a reason for us to be concerned about inflation”

So the headline employment data can look strong (and has) and you can still get a falling rate of inflation if capital isn’t forced to pay up for labor. And what do we see in hourly earnings? This month’s labor report showed one of the sharpest slowdowns of recent years with the rate of change slowing from 4.6% to 4.2%. I expect this to slow further and stabilize in the high 3% range during 2024. But for now the trend is clearly still to the downside and that is consistent with a labor market where workers have less negotiating power than capital. And that should ultimately flow through to lower rates of inflation.

I am a broken record on this by now, but this is not remotely close to what happened in the 1970s or 1940s when we saw large resurgences in inflation. Those narratives look dead in the water with wage rates falling the way they are. So, despite a relatively strong labor market, the underlying trends are consistent with a labor market that isn’t overly tight. You could even argue that metrics like full time employment, temporary help and the quit rate are consistent with a labor market that is loose. So don’t let the headline figure fool you into believing that the labor market is necessarily tight.

What does it all mean for the Fed and short-term fixed income investors?

This labor report gives the Fed some breathing room to wait on rate cuts. The labor market is strong enough that they don’t need to rush anything. Inflation is still moving in the right direction, but it’s been sticky enough in early 2024 that they don’t want to risk a resurgence in inflation from cutting too early. This is the ideal scenario for the Fed. They’ve managed to bring wages down and cool the labor market without causing a dramatic decline in jobs. And that means they don’t have to rush to conclusions and cut rates just yet.

All that said, the calendar for potential cuts is getting interesting now. I had been in the June camp and creeping to July, but now I am starting to think that November might be the first cut. And here’s the problem – I think we’ll be at about 2.5% core PCE by May and if we continue to get strong employment reports then the Fed’s going to be a little uneasy about cutting in June. So June is probably off the table. July is a maybe, but same basic story there where core PCE is still a touch too high to be certain about trend inflation. And then the next meeting is September which is just three weeks from the election. Will they initiate their first cut right before the election? Boy, I doubt it. I can only imagine the headlines there with people screaming that the Fed is working for the Democrats. And that leaves the November meeting and the December meeting which would mean two cuts in 2024.

It’s not necessarily bad news. We continue to see a very tough environment for anyone who needs credit, but we also see high interest rates for anyone living on a fixed income. So, I guess it depends on which one you rely on more because high rates are bad for new borrowers and great for savers….