Here are some things I think I am thinking about this week:

1) Should you replace your S&P 500 holding with Berkshire Hathaway?

I got a great question from my friend Simon, a financial advisor in Canada, who has been having a debate with some of his colleagues. It’s a timely one on the back of the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting and also because I am putting the finishing touches on my last book edits. In the book I discuss the Warren Buffett strategy in detail and I actually talk about Simon’s question, which was “should we replace something like the S&P 500 with BRK?” I love this question so let’s dig into it a little bit.

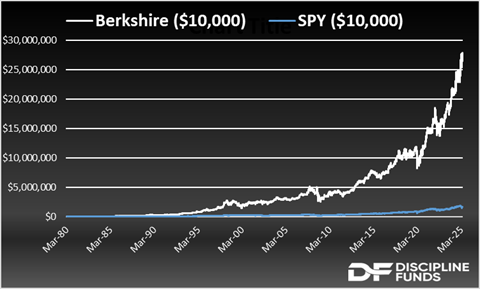

The general thinking here is that Berkshire is a proxy for a broad index fund because it’s so diversified. But it has a better track record than something like the S&P 500 and also has the benefits of being more tax/fee efficient (because it pays no dividends) and has no expense ratio. Just going off the historical data it’s kind of silly to compare the two positions as Berkshire has trounced the S&P over the last 45 years. But that’s not nearly the whole story.

Berkshire’s a strange beast because I’d argue it’s a VERY different animal today than it was 50 years ago. The big benefit of owning Berkshire 50 years ago was that you were getting a much more concentrated entity with acute private equity exposure. In fact, in the book I argue that one of Buffett’s keys to success was that he was really early to the private equity game. He’s best known for his big public stock positions, but the secret sauce to Berkshire was his early private equity positions and the way he leveraged his insurance float. But in the last 20 years Berkshire, largely due to sheer size, has become much more similar to a public equity index.

After beating the S&P 500 by 11% per year from 1980 to 2000 that margin shrunk to just 1.4% over the last 20 years and 1% in the last 10 years. In fact, Berkshire and the S&P 500 are virtually indistinguishable over the last decade and with the exception of the last 6 months Berkshire spent most of this period underperforming despite virtually identical risk adjusted metrics.

In short, I am not convinced by the argument that Berkshire should replace a more diversified S&P 500 holding. Despite the lower fees (which are negligible to begin with) you still have more concentration and acute key man risk in Berkshire. And the likelihood for much better performance going forward is unlikely given the sheer size of Berkshire and its increasing correlation to the broader economy. You probably can’t go wrong holding both or using Berkshire as a satellite instrument to complement the S&P 500, but I do not think it’s a proper replacement given its low, but outsized risks relative to the potential future rewards.

2) Are the protectionists winning?

In today’s excessively online world narratives rule the day. If you win the media narrative war you have the upper ground in the policy debate. And that’s what I believe we’re seeing with this whole tariff debate. We should be clear – the rationale for tariffs is bad. It’s always been bad. But there is just enough truth to it and there’s enough frustration with the economy that people are saying “well this ain’t working so let’s try this other path“. It’s frustrating for me to watch because I believe 95% of the worries about the economy stem from inequality. And while 5% of inequality is the result of free trade the other 95% is due to the tax code and housing regulations that have now priced people out of the most important asset in the economy. And protectionism and regressive tariffs will definitely not fix inequality. And so I think we’re implementing the wrong prescription based on a flawed causality.

When I wrote my first book 10 years ago I wrote a section about how a Capitalist economy is similar to a poker game in that a few players will end up getting all the chips if you let the game play its natural course. That is, Capitalists are inherently monopolists. A good Capitalist wants to control more and more profits. This is a good thing! To some degree. It can also be a bad thing because, in an extreme case, it could reduce competition and more importantly, it could cause social upheaval. Keynes hated Socialism, but he always worried about how Capitalism could defeat itself by causing so much inequality that the people would reject the system and replace it with something more Socialist. So he argued for targeted government in a way that would help redistribute the chips at the table to avoid that outcome.1 And we’re very much on the precipice of the sort of upheaval that Keynes worried about. Except, instead of Socialism, we’re moving to protectionism.

The worrisome thing is that we’ve misidentified the causal factor of the inequality and now we’re engaging in a more protectionist solution. And that narrative is winning. For instance, here’s Joe Nocera, who is a famously left of center NY Times columnist and outspoken critic of Donald Trump, saying that the protectionists have been “vindicated”. I am not sure how anyone can claim vindication of this tariff policy given that we just had the weakest GDP reading in years thanks primarily to the trade issues. In fact, by my accounts the protectionists have been dead wrong for 30 years and were virtually buried during this period. Over the period of free trade the US economy grew stronger and stronger. The list of accolades is almost too long to keep track of:

- The USA is #1 in GDP per capita in the G20.

- The USA is #1 in absolute global GDP.

- The USA is #1 in total wealth.

- The USA has 50% of all global wealth when excluding the G7.

- The USA has 60%+ of all stock market capitalization.

- The USA has 55%+ share of global reserve currency.

These are the metrics of a wildly, outrageously, fantastically successful economic system. The idea that poor countries took advantage of us in this system is simply preposterous. And yes, we allowed the distribution of that wealth to become a domestic inequality problem, but blaming the free trade system for inequality is like blaming the water when your bathtub overflows. Yeah, that’s what water does when you let it run uncontrolled! If you fail to control the distribution and level of it then that’s on YOU, not the water.

Anyhow, Alex Tabarrok and Dominic Pino have excellent articles countering the Nocera piece. But I am not sure it matters because it feels like we’re moving ahead with a much more protectionist agenda in the future and that’s in large part because the protectionists are winning the narrative war despite vast evidence that the narrative is a bad one.

3) If economists are so dumb why are they so rich?

There’s been a big push against “experts” in the last 15 years or so. This is wide ranging, from doctors to economists. And it stems, in my view, from a growing mistrust of institutions, which I discussed here. Some of this is warranted, but like the tariff debate it also appears to be a situation where shreds of truth lead people to make sweeping generalizations.

I see this most acutely in the response to the way people view economists. Following the financial crisis people grew to increasingly distrust economists because our economic system came so close to collapsing. Economists didn’t cause the housing bubble and the wild speculation that led up to it, but they got broadly blamed for their models which didn’t properly account for the financial system and failed to predict the risks. Again, some of this was warranted. I was a pretty vocal critic of mainstream models like the “money multiplier” when we responded with policies like QE. And it’s true – I think mainstream economic models failed to properly understand the financial system and the risks it posed to the economy. But these are unfathomably complex issues and you can’t conclude that all of mainstream economics is bad just because it’s imperfect. For example, doctors still fail to predict and cure most cancers, but that’s because the human body is a hugely complex system and modern medicine, despite all its innovations, is imperfect. We shouldn’t just dismiss all medical experts because it’s an imperfect practice.

Anyhow, I was laughing at this because I’ve seen a narrative multiple times in the last few weeks where someone says something like “if economists are so good at understanding the economy then why aren’t there a lot of rich economists”? I laugh because I actually studied the wealth of many famous economists for my new book. And aside from the fact that the median income of an economist is $120K, twice the national average, here is a list of a few pretty rich economists:

- A guy named Warren Buffett, who got his Masters Degree in economics and is arguably the greatest money maker in human history.

- William Sharpe, a Nobel prize winner who sold his firm Financial Engines for $3B.

- Gene Fama, a Nobel Prize winner who is a Principal at DFA, a firm that runs more than $700B.

- Richard Thaler, a Nobel Prize winner who runs his own $30B asset management firm.

- Paul Samuelson, a Nobel Prize winner, was an early investor in Berkshire Hathaway, Commodity Corps and RenTech.

I could go on and on here. The list is long and economists as a whole are a very wealthy group of people. Of course, not all of them made their money implementing mainstream macroeconomics, but there appears to be a pretty strong correlation between wealth and a general understanding of economics. So it makes me wonder – if economists are so dumb then why are they so rich?

That’s all I got for now. I hope you’re having a great weekend and as always, stay disciplined!

1 – It’s strange that some people associate Keynes with big government and Socialism because he was incredibly insulting of Marx and his work. He was boisterous about being a rich upper class Capitalist and much of his writing appeared to look down on the working class. I suspect he’d be aligned with a moderate Republican view of politics if he were alive today.