Here are some things I think I am thinking about this weekend:

1) Updating the Roche Recession Rule.

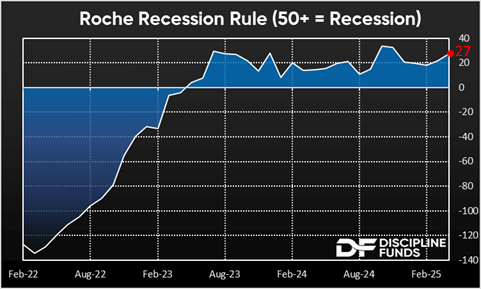

I’ve updated the very, very famous Roche Recession Rule, which was very famously named by me and for me. I highly recommend creating your own recession rule. Unfortunately, it won’t have the same ring to it unless your name starts with an R. Anyhow, here’s what the update looks like.

This chart, which updates at the Macro Dashboard, is 4 week jobless claims plus the U1 unemployment rate on a YoY % basis. Despite its simplicity it has a perfect record predicting recessions going back to 1965.

As I’ve noted a few times in recent weeks, you can’t really have a recession without a soft labor market and we’re not seeing that so far. But things might be on the verge of getting more interesting here as the tariff impact starts to filter into more of the data. Last week’s claims data was the first decent spike in a while and continuing claims hit a multi-year high. But I’d still argue that the current Recession Rule is consistent with a soft, but not a recessionary environment. It will be interesting to see where this one trends in the coming months though because I wouldn’t be surprised if it has some upside bias.

2) Bad Tariff Narratives.

Speaking of the labor market – we got a pretty decent labor report on Friday. The headline was 177K new jobs, but the prior two months were revised lower by 58K. Wage growth moderated a bit, but it was mostly boring. Not too hot, not too cold. Perhaps not “just right”, but there certainly wasn’t anything too alarming. And now I can hear the bad tariff narratives building as people start to say analysts overreacted to the tariffs. Au contraire, bonjour!

First, the performance of the stock market and short-term economic data doesn’t give us any definitive understanding of the tariffs. But even there the evidence still says the tariffs have been a net negative. The stock market is still down 8% from its highs in February when the tariff talk really ramped up. And then Q1 GDP was the weakest in years and Q2’s early readings are for 1.1%. This isn’t great. Sure, it’s not the end of the world, but the main point I’ve been making about tariffs over and over again is that they make you worse off than you otherwise would be.

Milton Friedman called tariffs an “invisible tax” because you might think you’re doing well because you don’t see the counterfactual. For example, what if we’d had no tariffs and the stock market had never dipped? Or what if GDP had grown at 2.5% in Q1 and Q2. In these cases we’d be better off than we otherwise are. And that’s the whole point. You can have absolute growth with tariffs and still be worse off in relative terms. But you might not know you’re worse off in relative terms because you don’t see the counterfactual.

In any case, this has a long way to play out. I am sure glad it seems to be de-escalating and that the worst case scenario appears to be off the table, but so far the short-term evidence is still pointing to tariffs having been bad. Sure, there might be some long-term gains, but there’s no denying that the data in the near-term doesn’t justify some of the positive spin I am reading.

3) Why Temporal Diversification Works.

This is going to sound a little strange, but the recent stock market downturn has been one of the more enjoyable ones I’ve endured, primarily because it’s vindicated the Defined Duration methodology. I constructed this model for asset management during the Covid downturn and didn’t really formalize the methodology until the last few years. I suspected it would work well in a frightening market environment, but I wasn’t really sure because I’d never seen live portfolios tested in real-time. And I’ve had numerous clients reach out to me to say how calm they’ve been specifically because they have such a sound understanding of how their assets match their financial planning needs. That’s really nice to hear since the whole point is to give people greater certainty of time, especially when markets become especially uncertain.

I was trying to conceptualize why this is an important financial planning approach and I think the explanation below might be helpful.

We typically think of diversification as a tool to mitigate single entity or single asset risk. That is, if you buy 25 stocks instead of 1 stock then you’ve largely eliminated the risk that any single entity can blow up your portfolio. But stocks are still highly correlated because they’re all corporations that are most likely correlated to the economy to some degree. So, when a recession hits the vast majority of stocks will become correlated to varying degrees. Owning the entire S&P 500 doesn’t give you certainty during a bear market even though the index is extremely diverse.

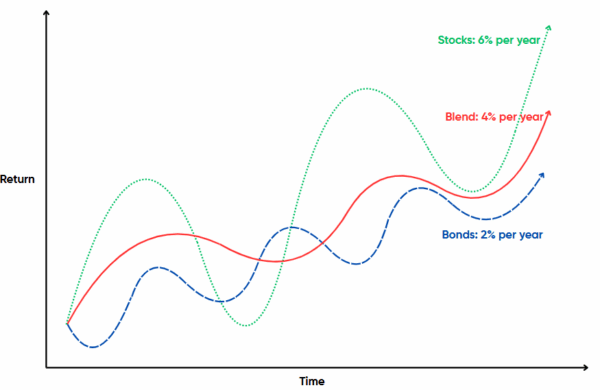

If you want to create diversification from that economic risk then you need to add other types of assets whether that’s stock from different economies or assets that earn their returns in totally different ways. For example, adding a 10 year bond gives you asset class diversification because that 10 year bond will generate returns in a much more stable way compared to stocks. But most of us don’t really want diversification of asset classes. We really want diversification of TIME because we want certainty. And layering in lots of longer duration assets doesn’t solve the problem of time in a portfolio. That is, when you blend a 10 year bond with a 17 year equity allocation with a 28 year gold allocation (as measured in my DD methodology) you aren’t getting short-term certainty even if the assets are inversely correlated. You are getting more certainty than holding any of these components individually, but when that equity piece becomes uncertain you aren’t thinking in 17 year time horizons. You’re probably thinking in 17 minute time horizons.

For example, if the stock market is a 17 year instrument that earns about 6% per year and the aggregate bond market is a 5 year instrument that does 2% per year then you’re very specifically diversifying not only across asset classes, but time. This can be visualized in the attached image. But the real magic happens here when you start to specifically add more and more time horizons and psychologically compartmentalize them as specific time horizons. Ray Dalio talks about using Risk Parity and portfolio optimization as diversifying across a sufficient number of uncorrelated assets. I’d reframe this. Yes, we all want to mix the highest return assets with the lowest correlation. But the problem is that the highest return assets are longer duration assets. And in my opinion, the true holy grail of investing and financial planning is creating certainty across time. And in order to achieve that you need to diversify, but very specifically diversify across different time horizons using the right temporally structured assets.

That’s all I’ve got for now. Until next time, be well and stay disciplined!