Here are some things I think I am thinking about:

1) Inflation STILL Isn’t Scary.

In the wake of Wednesday’s CPI report there were all sorts of scary narratives about how inflation is raging and we’re on the verge of a big second wave of inflation. I’m not much of a surfer, but if this is a second wave then it’s a pretty pathetic one so far. In fact, inflation has averaged 3.5% historically and CPI came in at 3%. So we’re not even seeing a “wave” that is above average height so far.

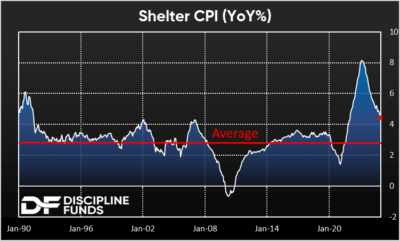

I know we’re not at the Fed’s target yet and we seem to be moving in the wrong direction, but in my view this story is still mostly about the trend in shelter. And the trend in shelter is definitively lower. Remember, shelter is almost 40% of CPI so it has a huge outsized impact on the directionality of these readings. And the latest reading is trending clearly lower, but still well above the 40 year historical average.

You might know that one of my big themes over the last few years is that the economy is mean reverting to its pre-Covid trends. So I expect to see a lot more disinflation from shelter which means that you need a huge offset elsewhere to counteract it. So far we’ve had some modest commodity inflation which is making the readings look sticky, but that needs to move MUCH higher in the coming year for it to offset any forthcoming shelter inflation. But I think any large surge is a highly unlikely outcome. The much more likely scenario is that inflation settles into a 2-3% range with downside risk if other components move lower in tandem with shelter in the coming years….

2) Are Memecoins Valuable?

There’s been an explosion in so-called “memecoins” in recent weeks. Of course, our President ignited the trend with the introduction of Trump and Melania coin, but there’s been a million other iterations as well. I will be blunt about this. These are bad assets that have no underlying economic utility and no reasonable value basis. Here’s why.

To understand this we have to understand what gives something “value”? It’s an interesting question. Similar to what gives something “beauty”? It can be highly subjective especially in the case of things like collectibles such as baseball cards or paintings. Collectibles fly in the face of classic economic cash flow generating value because they rarely if ever have economic utility. Stocks, for example, often become more valuable with time because their underlying cash flows are derived from real economic utility. As profits grow the presumably scarce shares become more valuable. Behavior can impact the volatility of expected value, but there is typically an underlying driver of long-term value, especially when done thru something like an index fund which reduces single entity risk.

Collectibles are primarily perceptive value, typically nostalgic value. Some commoditized collectibles (such as gold coins) blend economic utility with nostalgic value, but this isn’t true of many/most collectibles. We don’t love the Mona Lisa just because we perceive it as beautiful. It harkens back to an era (the Renaissance) and person (da Vinci) that was transformative for our species and the way we perceive and value the importance of art in our culture. Most paintings are only valuable to the person who makes them. My daughter’s drawings are terrible, but I personally love them, I will keep many forever, but they are only valuable to me. In order for it to become valuable to the culture it must transcend personal perceptions of value and become culturally valuable in a nostalgic manner.

Memecoins not only have zero nostalgic or social value, but they also derive zero value from real economic utility. They are a purely speculative instrument. I have no doubt some Memecoins could achieve a degree of nostalgic value. But finding that coin isn’t like looking at a balance sheet of a successful company with economic utility and cash flows. It is more like living in 1900, having no idea who Honus Wagner is, whether he will ever be a good baseball player and trying to pick that specific card out of the thousands that will be produced during the early 1900s before his card is produced in 1909. Oh, and then you have to keep that card through numerous traumatic economic events and be patient enough for it to accrue its uniquely special value. This is more like playing the lottery than anything else. Fun? Sure, but a high probability and productive allocation of capital? Unlikely. Memecoins are the same basic thing.

3) Venture Capital Macro

I’m sorry to generalize about venture capitalists, but the loudest ones on Twitter appear to subscribe to a uniquely misinformed version of macroeconomics. For example, Jason Calacanis, who is clearly a savvy micro investor, posted this on Tuesday:

We see this sort of commentary a lot from Jason and the other VCs on the All In podcast, which is a very good podcast, by the way. And look, these guys are clearly brilliant. But they’re also not macroeconomists. VCs focus on micro specialties and these guys are very good at it. But there’s this thing about macroeconomics where anyone who comes across it tends to think it’s simple and obvious because, well, we all engage in the macroeconomy on a daily basis. We all have experience with it. But I’d argue that macroeconomics, while seemingly intuitive, is one of the most complex fields in science. Heck, it’s so complex that it’s not even considered a hard science because you have elements of hard science blended with social sciences like psychology. The economy isn’t just a mathematical equation conforming to laws like supply and demand. It’s a system that tries to conform to laws of economics that is also driven by emotionally irrational people. This is why macro is so hard and it’s why macroeconomists rarely agree on everything.

Anyhow, I see this error a lot in macro and as far as macro concepts go I’d argue that this is one of the easier ones to understand and yet people still mess it up all the time. First, an individual household is nothing like a government or any large aggregated sector. This is just a basic (and common) fallacy of composition. You can go bankrupt from watching too much Netflix, but the aggregate household literally cannot and actually relies on perpetually increasing borrowing in the long-run. The same basic fact is true of a government. The government is a huge aggregated sector comprised of thousands of individual components. It can’t run out of money any more so than the aggregated private sector can.1

Of course, it’s more complex than that. Just like the aggregated household sector cannot excessively borrow in perpetuity, the aggregated government sector cannot excessively print money in perpetuity without potential problems along the way. But the funny thing is, when you understand the true solvency constraint of aggregated sectors like the government (inflation) then you get into a whole other debate that macroeconomists don’t agree on – inflation. And that’s why macro is so hard. It’s like a never-ending series of impossible puzzles that are constantly changing and getting shuffled by the irrational people trying to understand the puzzle. I don’t know what my point is here. I guess it’s that you need to be careful where you get your macro analysis from….

Anyhow, that’s enough from me for today. I hope you’re having a great week. And as always, stay disciplined!

1 – It can run out of money it doesn’t produce by operating a gold standard or by borrowing in a foreign currency for various reasons. And it can most certainly run out of money in real terms as hyperinflation is evidence of a collapse in demand for money. But in purely nominal terms it’s silly to talk about the government running out of money.