You just have to love the short-term overreactions of Mr. Market. Just two months ago we get a weak employment report and investors are panicked that the Fed is too tight. Then we get a strong employment report in September and investors are panicked that the Fed is too loose. In May the 10 year interest rate was as high as 4.75%. By September it was as low as 3.6%. Today it’s bounced back to 4.2%. And as rates tick higher in recent months there’s been a growing chorus about how “bond vigilantes” are going to teach the Fed a lesson. This has been especially loud coming from Stanley Druckenmiller, Paul Tudor Jones and Elon Musk. The basic narrative is that bond markets will teach the Fed and US government a lesson about reckless spending which will drive up interest rates and bankrupt the USA. Except there’s a huge problem in this narrative – the bond market has a lot less control over interest rates than this story would have you believe.

We should debunk one myth right off the bat. When Musk says the US government is going bankrupt like a household he’s quite simply misunderstanding how the monetary system works. Individuals go bankrupt. Large aggregated sectors do not. For example, the aggregated private sector cannot go bankrupt. The US government is a huge aggregated sector in the US economy. It does not go bankrupt. In the aggregate it can print money to fund all spending and it cannot run out of this money unless it borrows in a foreign currency, which it doesn’t do. Of course, it can cause wildly huge inflation. We know that after Covid, but comparing the Federal Government to an individual is just wrong.1

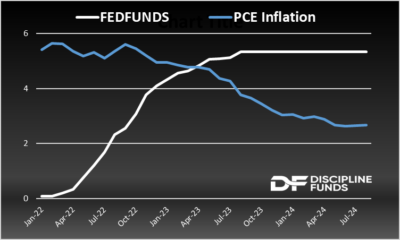

Of course, you might say this is all semantics. High inflation is a form of default. I don’t necessarily disagree! But when we assess the burden of the national debt we are really assessing the risk of inflation that comes from that debt. So, is the interest on the national debt causing an inflation problem? I think the evidence is very clear on this – no. Just look at the impact of raising interest rates when compared to inflation. If anything, it looks like raising interest rates causes inflation to move down, not up.2

But what about those pesky bond vigilantes? Aren’t they finally going to show up and teach the Fed a lesson? I don’t see it. I don’t even see how it’s possible. For example, the Fed is the reserve monopolist. So, as I’ve explained in the past, they have absolute control over something like short-term interest rates. The market quite literally cannot force them to change this rate because the market cannot compete with the Fed. If a bank tries to set the short-term interest rate the Fed just comes in and smashes them with their bottomless pit of money. Banks know this and so they do not fight the Fed. Of course, this is not true at the long end of the curve because the Fed lets the long end float. As I’ve explained before, the best way to understand the yield curve is to think of the Fed as a dog walker who has absolute control of the leash at the handle and allows the dog to wander further out the leash. The Fed has absolute control over the handle (the Fed Funds Rate) and lets the 30 year wander from side to side, but still within a certain control. It might look like the dog is walking the Fed, but the Fed always has the ability to pull that leash in and grab that dog by the neck. This is what “yield curve control” would look like and if the Fed entered the market for 30 year bonds and started explicitly setting a target they could drive that rate to whatever they wanted. But they let it float a bit. And smart bond traders still know that the 30 year bond is ultimately just a prediction about where the Fed will be on average over the course of 30 years. And that’s where this gets a little more interesting.

If inflation were to surge to 10% again then the Fed would have to react. What would happen there is the 30 year bond would start to move higher and signal to the Fed that they need to move. It would be similar to a large dog pulling the owner around. The owner has to respond. And the Fed would absolutely respond to a large surge in inflation. So, when inflation is high you can think of the dog as having more control and when inflation is low you can think of the owner as having more control. But the owner always ultimately has control over the dog. It just depends on whether the owner is willing to assert control. In other words, even if inflation jumped to 10% the Fed could still say “screw it, we’re leaving rates at 0%”. The bond vigilantes could kick and scream all they wanted, but if the Fed entered the market and pegged rates at 0% while inflation was 10% then rates would fall to 0%. This would be a terrible idea and it would never happen outside of something like a war-time emergency, but I am just communicating the concept.

Back to Druckenmiller and friends. This seems to be a pretty persistent thing with Druckenmiller. For example, I wrote nearly this exact same article 11 years ago in response to a WSJ op-ed in which Druckenmiller said the exact same thing. He said the USA was bankrupt and that the Fed was too loose. The 10 year yield was 2% at the time, the Fed was on 0% and rates would slowly drift lower until we got the Covid shock 8 years later. It was a dreadful prediction. I think the same exact thing is happening now. Don’t get me wrong. Druckenmiller is one of the all-time great investors, but betting on US government default has been a bad bet for a very long time. In my humble opinion, the error in this analysis is two-fold:

- Assuming that interest payments are problematic – they are not because the Fed can control them with a dial and also because high rates put DOWNWARD pressure on inflation.

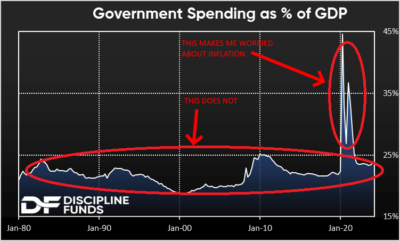

- Assuming high inflation must result from government deficits. I think it’s absolutely true that large deficits put upward pressure on inflation. I’ve said this a billion times during Covid. But government spending is 23% of GDP. That’s the same level it was at in 1982! And while it’s a large portion of aggregate spending we should remember that 77% of spending is coming from OTHER sources. In most cases, it’s much more efficient sources such as the most efficient corporate machine the human race has ever seen (corporate America).

Again, don’t get me wrong. When government spending explodes to 45% of GDP like it did in 2021 then big inflation can come from this because the government becomes the primary (reckless) spender in the economy. But that’s not the case today. Government spending as a percentage of GDP is about the same as it’s been for most of the last 40 years. So it begs the question – in an economy like the USA does the government drive inflation or is the government driving a small amount of inflation that is not as important as other factors in the economy? In my opinion, other factors are driving the secular inflation trend and that includes:

- Huge innovative efficiencies being driven by corporate America that exert downward pressure on inflation.

- Demographic changes that are turning America into an older and slower growing population.

- Inequality which is exerting pressure on those with the highest marginal propensity to spend.

If anything, it takes huge deficits to offset these three huge trends. It takes something like a Covid stimulus to result in big-time inflation. Otherwise, the government, even with its currently large deficits, cannot create high inflation without exploding the deficit again. Will that happen? It’s certainly a risk. But it wouldn’t be my baseline estimate. If anything, the deficit is likely to shrink in large part because the Fed is going to cut rates in the coming years.

So, long story short – the bond vigilante narrative is overblown. Does it mean we don’t need to worry about government spending and inflation? No, I think investors should continue to protect themselves from inflation, even if it remains low. But we also shouldn’t blow this out of proportion and feed into hyperbolic narratives about how the USA is on the verge of bankruptcy.

1 – I sometimes take digs at MMT people for the sloppy aspects of their theory, but this is one thing they’re generally pretty good about communicating. Comparing a household to the federal government is silly.

2 – I think it’s useful to be careful about the difference between high inflation and a benign rate of low inflation (as I described here). The USA has prospered in the last 100 years despite persistent 3% inflation. We are by no means “bankrupt” and in fact the country is the wealthiest it’s ever been. On the other hand, we also know that very high inflation is a form of default where consumer demand for currency is collapsing and that is a de facto form of default”.