Here are some things I think I am thinking about this weekend:

1) The Passive Decisions of Active Index Funds.

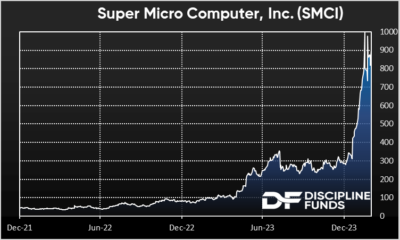

Super Micro Computer is being added to the S&P 500. This probably won’t impact the overall returns much (if at all), but it raises some interesting questions about the passive decisions of active index funds like the S&P 500. Yes, I said “active index funds” like the S&P 500. Long-time readers likely know my diatribes about the myth that is passive investing and this is a situation that makes that abundantly clear.

Super Micro’s case is especially interesting because the firm wouldn’t have qualified for the S&P 500’s $15.8 billion dollar market cap rule as recently as December. And the reason it qualifies now is because the stock has tripled in value in 3 months. Now, I am just a big dumb indexing advocate so I can’t speak to the validity of this firm’s individual financials, but it’s interesting in the context of what some people are calling an “AI bubble”, especially when you consider how controversial something like Tesla was. Tesla was a $500B company when it was added to the S&P 500. There are numerous other examples of firms that used to or currently qualify for the S&P 500, but don’t get added. Why not? We can’t be certain, but the S&P Indexing Committee is clearly making active changes as to how they add and delete firms. And not only are the additions somewhat subjective, but the rules themselves often have to change due to market circumstances. I recall one particularly glaring moment during 2009 when AIG became mostly owned by the US government and failed to meet S&P liquidity requirements, but they just ignored it.

It raises another interesting topic that I’ve written about in the past – the momentum factor of the S&P 500. Now, the S&P 500 is “the market” so it’s supposed to be factor neutral, but you could argue that another reason the S&P is so hard to beat is because it’s a momentum fund that adds new firms as they grow and deletes old firms as they shrink. This rules based process is systematic enough that other discretionary approaches struggle to keep up. Of course, this might not be an academic “momentum factor”, but it’s certainly a momentum based criteria for addition/deletion and might even make one question how long a firm like SMCI should maintain a certain degree of financial and market cap momentum before being added? Is 3 months enough?

What’s even more interesting in the momentum discussion is a comparison to the All World Equity Index. The S&P 500 has an 8% overweight in the tech sector relative to something like the FTSE All World Index. That’s a big overweight compared to the total global equity market. So you could argue that the S&P 500 has a momentum overweight due to its tech position and explains much of the outperformance relative to global stocks. It could also be a warning that the S&P 500 is earning a higher return by increasingly taking more risk….

Now, none of this is necessarily problematic in my opinion. The S&P 500 is hard to beat because it is diversified, low cost and doesn’t make a lot of changes. The active tilts of “passive” index funds doesn’t bother me because I know we’re all active and active is a sliding scale. What matters most is how damaging that activity is from the perspective of diversification, risk, taxes and fees. In the case of the S&P 500 it’s not very damaging if you know what you own. And what you own is a low cost, diversified index that’s likely to be riskier than something like the FTSE All World Index.

2) The Viktor Frankl Hack.

This one might not seem financially related, but I actually think this is a great framework for avoiding the trap of comparing yourself to “The Joneses” and letting money depress you.

I’ve talked a lot in the past about how having kids rewired my brain. It forced me to think in a multi-temporal sense which has completely changed how I think about asset allocation. I came up with the Defined Duration strategy because I realized I had no temporal structure in my own portfolio after the birth of my first daughter. That made me sit down and quantify the time horizons in a way that gave me financial predictability not only over my lifetime, but my children’s lifetimes.

But my kids also changed the way I approach problems. Having young children is very challenging and I think a lot of people go through it feeling lost or depressed. Worse, children will make you constantly consider your relative living standards to see whether other parents are giving their kids a better life. I’ve caught myself getting depressed about these things at times, but I’ve started doing this mental hack where I ask myself a simple question – “is this an opportunity to appreciate a difficult moment I can overcome?” We instinctively respond to difficult environments by being frustrated. The anger is the easy way to avoid solving the problem. But in Man’s Search for Meaning Viktor Frankl taught us that the environment cannot choose how you feel about it. You choose how to feel in certain environments. When we let difficult environments frustrate us or scare us we’re letting the environment dictate our emotional state instead of imposing our emotional state on the environment.

When my kids are being difficult I can choose to get frustrated or I can choose to appreciate the time I have with them and the lesson I can teach them in behaving better. When I fight with my wife I can view that as a flaw in our relationship or I can view it as an opportunity to solve a problem and make our relationship better. When I am exercising and fatigued I can choose to quit or I can see it as an opportunity to get a little stronger.

A lot of people feel depressed about the economy because life is hard. It’s hard having kids. It’s hard having two working parents. It’s hard working 40+ hours a week. But you know what? If you have kids and jobs you probably have a lot more to appreciate than you think. And even though those things might be frustrating at times they’re also constant reminders of the opportunities to appreciate the things we have around us.

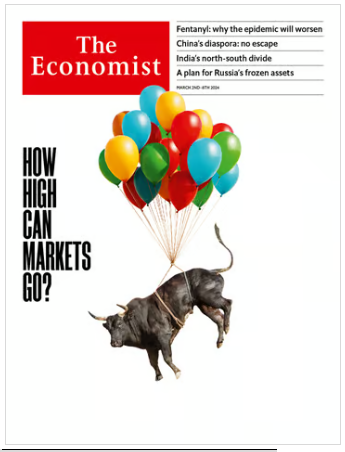

3) Bearish Magazines.

Financial pundits are all mocking The Economist magazine and its very bullish cover. There’s an old theory that magazine covers tend to be a contrarian indicator. Ah, if only it was that easy. The story is always more complex than pure sentiment and as the old saying goes, “markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”.

Still, it’s interesting in the context of the last few years because the S&P 500 is only up 11% since 2022. Factor in inflation and that return is actually negative. So it might feel euphoric because of the last 12 months, but maybe it’s not that euphoric. Then again, you do have signs of frothiness and high valuations. As an individual asset class I try not to waste too much time obsessing over the short-term performance of stocks. They are, as I’ve often noted, inherently long-term instruments that should mostly bought and ignored.

But an old study that was reported in, awkwardly, The Economist, found that after 360 days the bearish covers generated 18% returns and bullish covers were followed by -7.5% returns. And frankly, perhaps the very best thing that could happen to this stock market rally is that it dies down a little. After all, if we get really euphoric the Fed is going to have to respond and if they move higher from 5.5%, to say, 6 or 7% then things are going to get really interesting. And probably not in a good way.