One of the big stories of the year has been the lack of breadth in the performance of the US stock market. The so-called “magnificent 7” of Microsoft, Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta, Tesla and Nvidia have generated 71% returns. The S&P 500 is up 20%. And the remaining 493 companies are up 5%. The equal weight S&P 500 (which weights every company evenly instead of letting the market caps skew) is up 5% year to date.

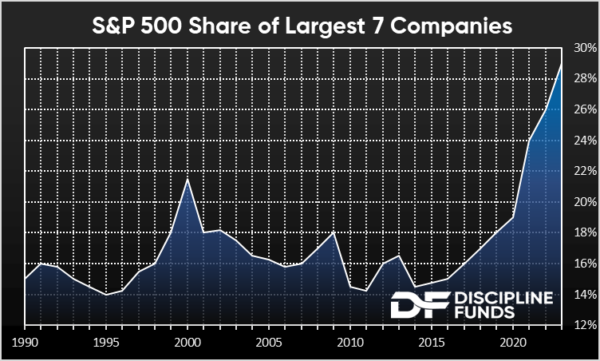

Looking at the share of market cap the seven largest companies are now a disproportionately large share of the overall S&P 500 at 29%. This is, by a wide margin, the largest skew in market cap that has ever occurred. The next largest share of ownership was during the tech boom when the seven largest companies grew to 22% of the index.

In terms of the aforementioned performance this is also an unusual period. The S&P 500 is beating the equal weight index by 15%. That also last occurred during the tech boom when the S&P 500 outperformed the equal weight index by 18%. The average divergence is -0.17% so these skews in either direction are unusual.

I don’t know what to make of all this to be honest. On the one hand you could argue that this is what makes market cap weighting so great. After all, the reason we’re generally advocates of market cap weighting is because it’s so hard to find those 7 great performing companies that drive the performance of the index. As John Bogle said, don’t bother trying to find the needles, just buy the haystack. It’s great advice.

The problem is that the haystack isn’t usually so driven by just 7 companies. So we actually have this unusual situation where you have single entity risk inside an index fund because the index has become increasingly dominated by a few firms. And if you get the opposite of what we’ve seen this year then the index will become unusually volatile (in a bad way) because of this single entity risk. The only other time the index was like this was in 1998 and we all know what happened in the subsequent 5 years. So, in a weird way you don’t want this concentration as an indexer because the whole point of indexing is to spread out your risk so that you own all the firms that perform good/bad, but also not so much of any single firm that it drives all the good/bad.

I find this especially interesting in the scope of the global stock market because these firms are all US firms and they skew the S&P 500 away from global cap weight. For instance, the FTSE All World stock index is 21% technology, but the S&P 500 is 30% technology. So the S&P 500 now creates a very large skew from global cap weight. In other words, if you were trying to be a truly “passive” global investor you’d actually have to offset your S&P 500 exposure to reduce its high exposure to technology. I am not generally a big advocate of “factor investing”, but this would be a perfectly reasonable situation in which you might consider offsetting some of the tech exposure by tilting away from tech in various ways.

Does all of this mean the index is “broken”? I hesitate to say that. But I do think this is all consistent with something strange going on that creates more potential risk than some people could be comfortable with.