There has been a raging debate in the last 15 years about the efficacy of Monetary Policy. I’ve been very vocal about certain aspects of this discussion, especially surrounding QE. My general view is this:

- When inflation is low and private sector debt is high, low interest rates near 0% have a limited impact on long-run inflation because monetary policy works primarily through the banking system and the demand for credit in such environments is generally muted. This is essentially what the last 15 years reflected and it’s why interest rates at 0% didn’t boost consumer credit much.

- To counteract this the Central Bank can also implement a Quantitative Easing program. But QE works primarily through boosting asset prices and reducing long-term interest rates, all of which run into the same problem in a low inflation and high private sector debt environment. Further, QE is a quantity tool and not a price tool. What that means is, unlike changing interest rates, the Central Bank lets the rate float. For instance, when the Fed buys $1T of T-Bonds they aren’t controlling the yield curve. They are letting the long end float, but trying to exert downward pressure through sheer quantity. This does not work as well as a price setting tool where the Fed could, in theory, set the rate of 10 year T-Notes at, say, 0% and pin it. All of this explains why QE didn’t cause runaway credit and inflation.

Raising interest rates during a period of Quantitative Tightening is a different story because it can suffocate banks and reduce the demand for loans. If the demand for debt is already low then banks effectively reduce the potential supply of loans. This is what’s happening in today’s environment as can be see in total credit and total loans.

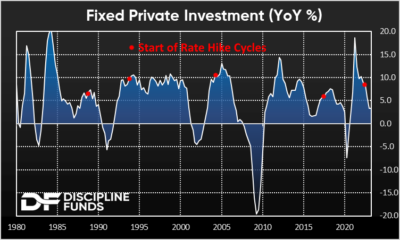

Now, you’d expect this to impact the economy primarily through real estate since most lending is real estate related. And yes, real estate has weakened materially, but it’s not as weak as I’d expected. At least not so far. But there are still signs that higher interest rates are having a very material impact on the broader economy. For instance, if we look at fixed private investment and private residential investment, it’s clear that the credit cycle is biting. It’s impossible to know where we are in the credit cycle, but the slowing demand for credit is one reason why we’ve argued that this would be a year of disinflation and “muddle through”.

As you likely know, this is all especially important if you’re a regional bank. We don’t need to highlight that story given the turmoil in the banking system. But the impact of Monetary Policy in the banking system is undeniable at this point.

Then again, none of this is translating to inflation falling as fast as many hoped. That could be partially explained by fiscal policy which has remained relatively large despite higher interest rates. But it’s also a “long and variable lags” story. It takes time for the credit markets to adjust because every contract in the credit market has a specific time function attached to it. So, if you have a 2 year loan outstanding Monetary Policy probably didn’t impact you at all. But when that 2 year term comes up you’re going to be refinancing in a completely new environment. This is essentially what’s happening today.

The bottom line is, the Fed’s policies are working. The financial markets are impatiently gyrating violently over the last 2 years (going largely nowhere) as they try to decipher all of this. And while Monetary Policy is not working as fast as we’d hoped, it’s clear that it’s working through the traditional channels.