Here are some things I think I am thinking about at the end of this weekend.

1) Team Transitory Won (NOT)!

It’s been over 3 years since I explained why the term “transitory” shouldn’t be used. And yet Paul Krugman is still out here saying inflation was transitory. Except he’s calling it “long transitory” now. The basic narrative is that the rate of inflation has now reverted back to its pre-Covid levels. It was all “transitory” and just took longer than expected. But I find this narrative pretty disingenuous because the entire reason for saying inflation would be transitory was based on the theory that inflation was all supply driven. That is, the inflation would be self correcting and “transitory” which wouldn’t require a huge policy response. That was the Fed’s thinking in 2021. But as it became clear in 2022 that the inflation was not just supply driven the Fed felt the need to abandon the transitory narrative and attack inflation with an aggressive demand side response.1

The “long transitory” narrative completely distorts what occurred over time and why the Fed and other economists said inflation would be transitory. As it turned out, we now know that the huge amount of government spending did create excess demand that required a large policy response. And so the rate of inflation came down, but only because the Fed abandoned the transitory reasoning and recognized that an aggressive demand side response was necessary.

And look, I am not trying to downplay the very real economic progress we’ve made in recent years. Things have been stronger than expected. But I also think it’s a bit out of touch to dismiss the very real burden that this inflation imposed on people in recent years. At the same time, it’s important to critically analyze the causation and response here because the economists who claimed fiscal policy didn’t cause inflation turned out to be wrong. And understanding causation here is an essential part of understanding how policy can be utilized to resolve potential problems.

2) 2 Myths That Just Won’t Die.

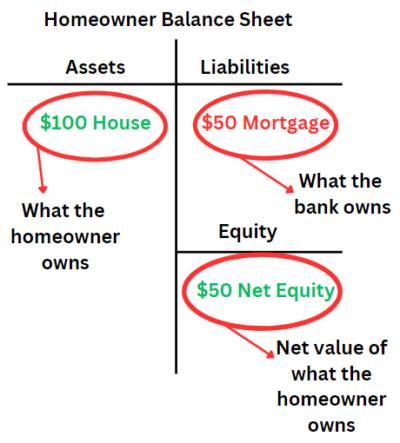

I use Twitter as a real-time news source and research resource. When you curate a good feed it’s just an unmatched resource for access to real-time smart takes from financial professionals. But boy can it be a hellsite at times. For example, in the last few weeks I’ve seen multiple huge Twitter accounts claiming that the bank owns your house when you have a mortgage. Unfortunately, it seems like an intuitive narrative that, if the bank can kick you out of your house for not paying your mortgage then they “own” the house in some sort of indirect manner. But this is incredibly misleading.

Now, I am sure the smart readers here know this, but the accounting and legality of this is very specific and we should be absolutely positively clear that the bank does not own the house. You own the house asset as dictated by the title. If you have a mortgage you also own a liability for the amount of the mortgage. You sign a promissory note to pay $X over a certain period. This note is a claim against the asset. The residual is equity which is reflected solely as yours since you’re the owner. The bank does not participate in upside or downside of the asset price change because they do not have ownership of the asset. They have a (usually) fixed claim against the asset. “Ownership” of an asset is directly tied to equity interest. If you do not have equity interest in an asset then you do not own that asset2

To put some figures to this consider that someone owns a house worth $100 and has a $50 mortgage on that house. They own the $100 house asset and the bank owns the $50 mortgage asset. The net equity value of the homeowner’s assets and liabilities is $50. Importantly, if the house increases in value to $200 then the homeowner alone nets the $100 gain because they are the owner.

So long as you pay your mortgage you alone own the house. And as with everything you might try to buy, if you do not pay then you will find out that you do not own that thing. The bank has the legal right to enforce that promissory note and that could involve foreclosing on your house. Again, if you don’t pay for things then you don’t own things. Anyhow, I was surprised by how widespread the confusion on this matter was so hopefully that clears things up a little.

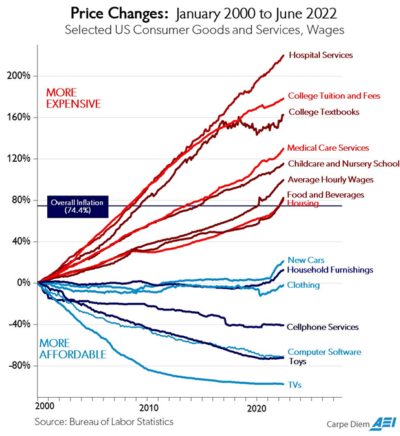

In response to one of my comments on Twitter someone posted a second myth that was unrelated, but is also widespread. This is a chart you might have seen going around scare mongering websites at times. The image is depicted to portray inflation as some sort of disastrous situation where our “necessities” have become unattainably expensive. I’ve written about this a lot in the last 10 years and it’s counterintuitive, but charts like this are not a sign of declining living standards and actually reinforce how good our living standards are becoming. Let me explain.

100 years ago things like college and health care were considered luxuries. Items like shelter, clothing and food were the primary “necessities”. But as our living standards have improved clothing and food became an increasingly small part of our disposable incomes. As our living standards improved more and more items became “necessities”. The fact that college and healthcare are now considered “necessities” is a good thing as it’s a sign that our living standards are improving as these luxuries become more attainable for all. But it’s also unsurprising that these items are the ones appreciating in price the fastest. That’s just basic economics and the chart here reflects a nearly perfect demand curve with rising living standards where items that were once luxuries are transitioning to necessities. And as the demand for those items increases their prices will increase at a faster rate than others. So this chart doesn’t show declining living standards. It shows improving living standards!

Don’t get me wrong – I am not downplaying the very real inflation and cost burden that these items impose on people. I am just pointing out that these developments are part of what progress looks like. We should expect luxuries that are transitioning to necessities, to be much more expensive during that transitional period.

3) The Powell Pivot.

Well, Powell made it official at Jackson Hole on Friday – the Fed is cutting in September. Now the question will become how much do they cut (25 vs 50 bps), how often and for how long? My guess is that they will cut 25 bps at each of the next three meetings (Sept, Nov and Dec). But the more important point is that there’s now a clear change in policy directionality. The question is how long will this policy change last and how low will they go?

It’s waaay too early to venture a guess about this, but I think the Fed wants to get rates back down in the 2-3% range. That’s a point where savers can earn an inflation protected return and important benchmark rates like mortgage rates become reasonably affordable for consumers. So, we’re talking about 8-12 rate cuts depending on how low they go. In a “soft landing” scenario that will take several years. The outlier risk is that the Fed is behind the curve and ends up having to cut very rapidly and get us down to 2-3% in a more rapid sequence. So, right now I’d argue that we’re in the early stages of a multi-year rate cutting cycle with the outlier risk that the Fed is behind the curve and will end up having to cut rates much more rapidly.

It’s interesting to note that we don’t really know if they’re “pivoting” or backpedaling here. I’ve mentioned in the past that a pivot would be a controlled move en route to scoring a basket whereas a backpedal would be a turnover where they’re forced to backpedal on a mistake. We don’t quite know whether they’ve been too restrictive for too long or whether this remains a controlled “soft landing”. Time will tell.

NB – Speaking of inflation, check out my hedge against pumpkinflation. I love growing pumpkins for Halloween mainly because my girls love checking on the daily pumpkin progress. But I also laugh at the idea that growing your own vegetables is an inflation hedge. I can’t tell you how many hours or dollars I’ve actually spent growing pumpkins when I know they’ll just cost $5 in October. But it’s not the endgame that makes the progress so valuable to me. It’s the journey of growing the pumpkins that is so much fun. There’s a cheesy metaphor for life in there somewhere.

1 – I have at times said that inflation would eventually appear “transitory” in the sense that the rate of inflation would eventually fall. This is not what the original users of this term meant and I think some people have forgotten that the original premise for the transitory narrative was that inflation was a supply side event that didn’t require a policy response. That is, after all, a big part of why the Fed was late to the party and their abandonment of this narrative was also why they ended up raising rates so aggressively.

2 – If someone has a claim against someone else’s assets they do not necessarily “own” that thing. For example, when you have deposits at a bank the deposit is your asset and the bank’s liability. You have a claim against the bank and they are liable for paying you. But you wouldn’t go around telling people that you own the bank because you have a claim against the bank. It’s the same basic thing with a mortgage. They have a claim against your asset, but that does not mean they own that asset.