Here are some things I think I am thinking about.

1) The stock market boom/bust cycle.

How should we think about the bull market in stocks in the context of its Covid era rollercoaster ride? Should we get the urge to chase the current bull market? Should we get more defensive in preparation for another bust? The simple answer is that the short-term movements of the stock market should be irrelevant to your financial plan assuming you have a well constructed temporally diversified portfolio. So, if you establish the right process and framework for asset allocation you should be able to compartmentalize your assets so they’re specifically structured and insulated from behavioral biases, but still in accordance with your financial plan. If the current market environment makes you feel uneasy then you might have a portfolio imbalance that needs revisiting. But here’s how I think about this structure and process.

I created the Defined Duration methodology to solve the problem of time in a portfolio and construct specific time horizons for the purpose of financial planning and asset/liability matching. I personally needed this because my portfolio used to be a homogenous mix of assets that gave me little certainty about how much money I’d have at specific points in the future. Now, in theory an investor has infinite time horizons, but I find it easiest to simplify it down to 4-5 time horizons where an investor can construct a broadly diversified portfolio that helps them build a sound financial plan while also building out a portfolio that diversifies across different assets AND time horizons to cover all of their life needs. Insurance is largely optional and plan dependent, but I think of the other 4 time horizons as essential. They are the 4 essential pillars to constructing a temporally impenetrable financial fortress. Here’s the basic framework for this methodology:

0-2 years: liquidity needs, emergency funds, etc.

2-5 years: uncertain short-term spending needs like house down payments, car purchases, etc.

5-15 years: moderately long-term needs like near retirement planning, a child’s college tuition, etc.

15+ years: Long-term planning needs like retirement, estate planning, multi-generational spending, etc.

Infinite or indefinite: Insurance planning.

These time horizons should correspond to very specific assets. Here’s how I think of it:

0-2 years: Short-term assets that have a stable principal value. Things like T-Bills, money market funds, CDs, deposits, etc.

2-5 years: Short-term investment grade bonds and intermediate bonds.

5-15 years: Multi asset funds like a 60/40 or 40/60 fund work great here because the stock/bond blend results in a blended duration of roughly 8-12 years on average.

15+ years: Aggressive long-term assets like stocks fit best here. If you’re into it you can tilt to factors and spice things up.

Infinite or indefinite: Insurance policies, options, gold, Bitcoin, etc. These are all instruments that have super long durations in most cases and operate like forms of insurance of some sort.

The mix of these assets will vary depending on a specific financial plan and personal needs. I’ve personally found that investors who sufficiently cover the 2 short-term buckets will end up being able to take even more risk than they think in the longer buckets because the short-term buckets create a sort of barbell that optimizes certainty so much in the near-term that they can largely forget what the riskier stuff is doing in the short-term.

Using this framework the stock bull market is largely irrelevant to the 0-2, 2-5 and 15+ year time horizons because the short-term buckets are too short to rely on stocks and the short-term movements of the stock market are irrelevant in the context of a 15+ year holding period. But it’s a little more interesting in the 5-15 year time horizon because that’s the time horizon over which an investor must decide how much stock they want to own relative to their bonds, assuming they use the multi-asset model I propose. I like to use my countercyclical approach in this bucket because it helps create a little more certainty, but you could use 60/40 or anything that is considered to be a “balanced” approach to stocks.

Long story short, the stock market’s short-term movements should be largely irrelevant to your plan because if it crashes it won’t impact your short-term buckets and if it booms you’re not gonna feel the FOMO because your other buckets should benefit. The 5-15 year bucket is a little trickier, but should still be easier to manage because you’ll never be 100% exposed to stocks in that bucket. Basically, if you have a temporally constructed asset allocation the short-term moves of the stock market should be irrelevant because your portfolio should be behaviorally robust against any sort of extreme move in either direction.

2) Stock market gambling.

Sometimes I wonder whether our financial markets are the prudent savings pools I’d like them to be or whether they’re just an outlet for gambling. Back before the heyday of exotic financial products I used to just rip on things like the way some people view the stock market as a short-term trading instrument. But we’re seeing a growing trend in highly speculative trading assets. This week’s entrant to the party was the Battleshares relative stock ETFs. I have to admit I like the name and even the concept. They are basically taking two stocks and creating a pairs trade with a long/short position. For instance, maybe you love Google and hate Exxon. So the ETF might buy Google and short Exxon. You’ll get the relative return of the two instruments. Neat. But, also more like gambling than investing because stock picking is super hard and shorting is pretty much always a negative sum game in the long-run.

Look, I am not here to rip on ETF firms. I love ETF firms and I am hugely bullish about ETFs. And if there’s a market for this stuff then that’s awesome. I am not your dad and I am not going to tell you how to spend your money. If people want to gamble and take wild risks then that’s just great. I assume if you’re reading this you’re either an AI bot who is going to murder all of us or you’re a grown person who can make adult decisions. But I do wonder about this growing trend in highly speculative trading style products that look like they belong in a casino more than they belong on a regulated stock exchange. I don’t know if it’s the dad in me or the old man, but they’re both grouchy about people using these kinds of products. But then there’s a spark of youth in me that thinks this is kind of fun. And I guess that’s okay in very small quantities.

3) Entitled Brats.

Here we go. This is just going to be a full-on dad rant so get ready.

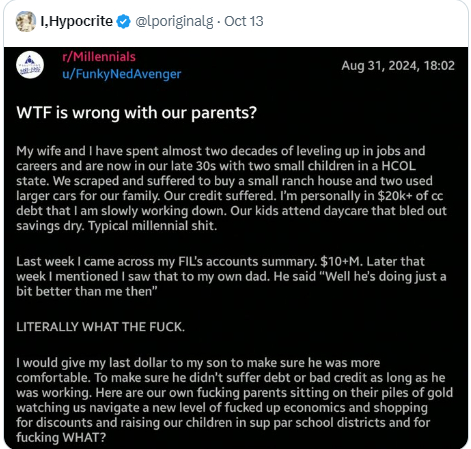

There was a great post going around Twitter this week from someone who was mad at their rich parents for not providing more financial aid. The basic gist of the story was that the person’s parents have tens of millions of dollars and the kids are scraping by without help.

At first I wanted to sympathize with this person. I thought, “yeah, these parents are jerks“. But then I thought about the most important thing that I’ve ever done in my process to becoming financially independent – avoiding bad debt. And that’s where I stopped feeling bad for this person. High interest debt might be the most reckless thing a person can hold. We should be clear – debt is not inherently good or bad. Low interest debt can be incredibly good. But high interest debt can be incredibly destructive. My parents didn’t teach me a lot about finance and money management, but one thing they hammered into my head was to always pay your bills. I have never missed a credit card payment because my parents hammered that concept into my brain. And I think that has been one of the most important things I’ve ever done financially. I’ve avoided the burden of high interest bearing debt and that forced me to spend a lot of my 20s and 30s living very frugally.

So, when I read that someone has $20K in credit card debt I struggle to feel bad for them because this strikes me as someone who is financially reckless. Why should they be trusted with millions, let alone even thousands of dollars if they have a proven track record of being financially reckless?

If this was one of my daughters I’d look at them and say “pay off that credit card debt, show me that you know the difference between good and bad debt and then we can have a discussion about how much money I’ll give you”. If you want to be entitled to someone else’s money then you need to prove that you won’t be reckless with that gift. That’s how I see it anyhow.

Okay, dad rant over.

Have a great weekend.