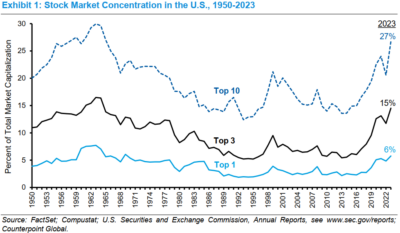

One of the persistent themes in recent years has been the high and increasing concentration in US stocks. In fact, the outperformance of US stocks has been driven almost entirely by large cap US tech names and the “Magnificent 7”. How worrisome is this and does it matter to your portfolio? Let’s explore this in a little more detail.

First, a bit of historical perspective. The current concentration is on the high side, but not unheard of. Michael Mauboussin recently published a piece for Morgan Stanley showing that the current concentration matches what we saw in the early 1960s. The 60s were a good period for stocks with 8.7% average annual returns. You could have entered the year 1960 worried about high concentration in stocks and it would have been a big nothing-burger for over 10 years.

And while history rhymes, it might not repeat. This time is not the same. And the difference is two-fold:

- The concentration in stocks is occuring much more rapidly.

- The concentration in stocks is happening during a period of high valuations.

As you probably know I am obsessed with the temporal based impact of everything in the financial markets. Time is really all that matters in the end. And the world around us is changing at an increasingly rapid pace. This is exciting, but also creates many unknowns. We seem to move from panic to euphoria much more rapidly than we used to. And we know that part of this is the simple reality of the fast moving world we now live in. Companies are dying and growing much faster than they ever have. And that’s especially true in the tech world. As Dartmouth showed back in 2018, a publicly listed firm had a 92% chance of being around 5 years from now versus just 63% as of 2018.

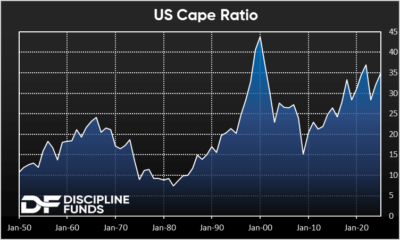

The pace of concentration is interesting because Mauboussin shows that falling concentration tends to coincide with lower annualized returns. But concentration is not a problem on its own. The question is whether the concentration is indicative of something higher risk or potential irrational exuberance. And that’s where valuations come into play. If we look at historical CAPE ratios the current environment looks very different from the 1960s. Not only have we had a very high rate of change in concentration, but we’ve also have very high valuations. This makes the current period look more like the 1999 concentration than the 1959 concentration. But we need to be careful making false analogies. After all, this isn’t the tech bubble all over again because the firms causing the tech boom are not just speculative wishful thinking. They are the most profitable entities that have ever existed. The fundamentals very much support their high valuations.

All that said, the rate of change is worrisome. The valuations are worrisome. But again, I think we need to bring time back into perspective here. After all, even the tech bubble wasn’t wrong. It was just early. The patient investor in tech in 1999 did just fine in the long-run. Sure, they had to wait a long while, but they did fine. And I think the current environment warrants the same kind of thinking. The current valuations in tech are not wrong, but it would be irrational to assume they’re not creating some unknown (potentially significant) risks that we don’t know about.

So, the conclusion is, how patient are you? In my Defined Duration model the US stock market is currently a 19 year instrument that should generate about 7.5% per year if you hold it for the full 19 years. If you’ve got a multi-decade time horizon none of this really matters. You should just be aggressive, keep enough around for liquidity/emergency needs and turn off the financial TV. But if you’ve got a short time horizon then this sort of environment warrants some risk management. While no one knows how this will all play out the one thing we do know is that high valuations combined with high concentration can mean high positive volatility and also high negative volatility. And so the takeaway is that stocks should be expected to be riskier than average in the short-term and if you’ve got a short time horizon then it’s prudent to try to diversify away some of this concentration just in case.